The whole sequence has been intense, cinematic, almost with a touch of Wiz-War. At the glacial pace of three cards per turn, we start to refill, but all I have to do is move - he needs slightly rarer attack icons. Then two: one more will finish that zombie. I'm on tenterhooks waiting to see what pain is coming and whether I can block it. Each turn requires a moment's planning on his part to maximise attack chances. The pressure on my hand is enormous: some factions have lots of additional card draw but the dead have little. Over the next few plays, it becomes a deadly, thrilling cat and mouse chase. I have the cards to block the first couple but then, on my turn, I'm short of ones to move away. His team targets my lone crystal-gatherer and start to shadow him up and down a corridor, playing ranged and melee attacks. Their plethora of attacks means I can then use another character to hunt down and kill a poor ranged character with only two health. The flexibility of the dead lets me snaffle an early crystal. With a much bigger board, it feels more open to variety. Without deckbuilding, it's easier to pick up. Which it does, but Wildlands has a lot more under the hood. Looks like I'm going to be playing the butcher again.Īfter going through the rules, my opponent comments that it sounds a lot like Shadespire. I pick an expansion, some undead, who have an unusually flexible deck but find it hard to capture crystals. He goes for a band of clockwork gipsies, whose deck has a lot of rally actions that allow adjacent figures to get activated together.

We unpack and pick some different factions. I find it in my usual foil for Star Wars miniatures. There is clearly a lot here to work with.

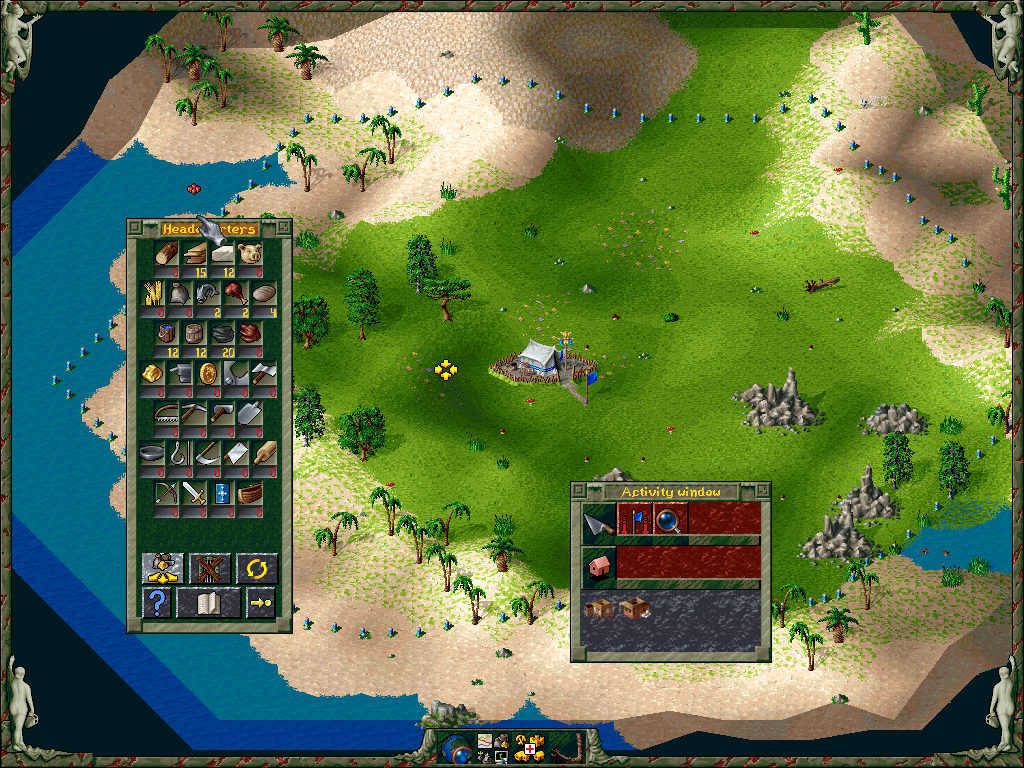

I win a quick, bitter victory and daughter walks away, unimpressed. These would give the mages the chance to flee and counter-attack but it doesn't happen. These are a bit like opportunity fire: you can play one after an action to take over for a bit, playing cards until your opponent's turn resumes. What the wizards should be doing is playing interrupt cards. There are no dice: each attack icon has one or more defence icons and so it becomes a case of a card for a card. They swing into action, hunting down and butchering the weak wizards. My mercenaries are brutal in combat so that's what I go for. It takes a while to learn to manage this handful of icons but after a while it becomes smooth. Given this regrettable misunderstanding, our first game is brief. So she puts them on the board and runs away. Her wizards are fast and have the potential for deadly ranged attacks, but they're fragile. My daughter doesn't seem to quite grasp this is a combat game where you earn points from knocking out characters as well as crystals. Then another, as I realise that since you draw three cards a turn you ought to play that many. Playing a card means you can take that action with the matching character.Ĭursing, I reveal another character so that I can actually do something. Each has a grid of character and action symbols like melee or magic attacks. Then I realise that my hand of action cards which I'll use to power the game don't match that character at all. Having no idea what I'm doing, I reveal a character near one of my crystals by placing its miniature on the board. The other five we swap, and they become the spaces where our teams' crystals will go, sparkling lumps of plastic worth a victory point each. Five we secretly assign to our characters as starting spaces, although they don't appear on the board yet. Each space on the dungeon board bears a number and we start out with ten number cards each. Still, it doesn't take long to get going. The game is simple but the rules are not well laid out. We open the rulebook and find, inevitably, it's not playable out of the box. I grab the other miniatures and their card deck from the tray, a motley bunch of mercenaries. She picks a faction of wizards with their book-toting golem, largely because it includes a humanoid owl called Hugo. Eldest daughter gets dragooned into my opposition. Riding a ridiculous high of enthusiasm I decide to put the "playable out of the box" bit to the test. Some months later, the real Wildlands causes me wild excitement when it drops onto my doorstep. He tells me it's easy to learn, playable out of the box, but with plenty of mechanical depth. It's clearly built on his wargaming roots but has evolved to become a quick-playing asymmetric game of fantasy combat. The more Martin Wallace tells me about Wildlands, the more impressed I get.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)